Defending the Professional-Managerial Class

Richard Hanania should give up his dumb libertarianism and be the earnest liberal he wants to be.

That the left half of the American political spectrum has higher “human capital”—smarter, more educated, more competent personnel—than the right half has been a structural fact of American politics for my entire lifetime, if not for most of the twentieth century. That is not to say that there aren’t smart conservatives or brilliant intellectuals with right-wing politics, but that the American conservative movement has been defined by a long history of constructing an “alternative” ecosystem where ideological purity and partisan loyalty trumped evidence and expertise.

I used to try to explain this to conservative family members back home as I was explaining it to myself in my early 20s, when I moved abruptly from one of the bastions of far-right evangelical movement conservatism into working in the mainstream media in DC and New York. As a still barely ex-conservative, it was obvious that all of my media colleagues had liberal politics, and that in some cases those amounted to partisanship for the Democratic Party. It was also obvious that they were first of all committed to journalism and truth, including when it was awkward for Democrats or complicated their own worldview. They thought it was interesting when the facts didn’t line up with what they thought, or an issue didn’t break down neatly along partisan lines.

I tried to articulate it many times before I got it right: the conservative critique of the liberal media, so central to the political worldview I grew up with and partly responsible for my interest in media in the first place, was right about the basic fact that most of the media was liberal-leaning, even “biased” in some sense. But that right-wing obsession missed the forest for the trees. I would say things like, “Of course the media is liberal, but liberal things are not ideological in the same way conservative things are. Ideology is in the background of liberal institutions, but it is the only thing in conservative institutions.” In the era of 2000s neoliberalism, liberal spaces were much more heterodox and open to dialogue with conservative arguments than the right-wing world I was familiar with, which for all its intellectual trappings still primarily groomed one to recite dogmatic mantras, misdirect, own and discredit. I saw it firsthand in the way very young conservatives were whisked into prominent positions in right-wing media and politics simply because they had the right beliefs; conservative institutions had to take anyone who hadn’t defected from the project by age 22. When people accused me of abandoning my beliefs, I would say, “It’s not even about the beliefs! It’s about the style.” In the broadest sense, it seemed clear that one side in the political discourse cared about learning, accurate information, and rational debate—all of the things my conservative education had ostensibly trained me for—and one side didn’t.1

I’ve been thinking back to that time the past few months as I reacted in disgust to a seemingly ascendent sentiment that the second Trump era—or the “vibe shift,” or the end of wokeness, whatever you want to call it—marks the entry into some glorious new era of free speech and cultural vitality. I thought about it as I started spending more time on Substack and picked up on a puerile anti-elite, anti-institutional animus, vastly disproportionate to the failings of its targets, that seems more prominent here than elsewhere. I thought about it again over the past few weeks as the headlines were dominated by the mass, indiscriminate firings of federal workers at the behest of a billionaire madman with no legitimate democratic authority or mandate.

And I especially thought about it when I realized how much I had been reading Richard Hanania.

“Why is everything liberal?” Hanania asked in a 2021 post that is now the most popular essay on his Substack. In a series of three posts, he advanced the argument that liberals are more idealistic and care more about politics, resulting in outsize influence not just on culture, but on public policy. Later the same year, Hanania had progressed to trying to explain why that was so. Rejecting Jonathan Haidt-style political psychology as too reductive, he turned to collective political cultures and their norms. “I want to present a new theory of American politics,” he wrote in a 9,000-word post. “Liberals live in a world dominated by the written word, while conservatism is something of a pre-literate culture. This can be summarized as ‘liberals read, conservatives watch TV.’” Hanania explicitly identifies with the right and sympathizes with Republican positions. “Overall though,” he wrote, “I can’t deny that my analysis generally makes liberals look smarter and more honest than conservatives.”

Hanania is an unapologetic elitist who harps constantly on the theme that the left has more “elite human capital” than the right. While this is certainly related to the right-libertarian obsession with IQ and biology, that is generally not the spin Hanania gives it in his commentary on the differences between the sides of the political spectrum. “When I discuss elite versus low human capital, I’m less interested in individual differences than in the kinds of communities and norms various groups of people create,” he wrote in 2021. “An important point to remember is that EHC cares more about status and ideas than money, so this is why they have such an outsized influence. And in many ways, they have better communal norms.” Even though Hanania shares some of the right’s critique of the ideas in the left-wing media, the university, and the Democratic Party, he still almost unequivocally thinks left-leaning institutions and their products are superior, both intellectually and morally:

EHC tends to have higher ideals, while LHC sees the world in zero-sum terms, and can only be inspired if it has an enemy to bash. Its favorite targets include minorities, free thinkers, sexual non-conformists, and of course, foreigners most of all. From this perspective, it is not surprising that conservatives are happier than liberals, because their “thinking” about politics, which they approach like a football game, is a kind of self-indulgence, based around the bonding experience of rooting for their own team and the idea that the groups they identify with are superior to others.

During the 2024 presidential campaign, leftists began to joke that Hanania was starting to sound like a resistance liberal. During “brat summer,” when I was briefly back on Twitter, he could be found posting clips of Kamala Harris events, wistfully contrasting their positive vibes with the bile of the online right. Someone on the left wrote—I unfortunately can’t remember who or find the tweet now—something like “Hanania’s feed is the strangest mix of the most insane takes you’ve ever heard and him hilariously, accurately owning his own followers.”

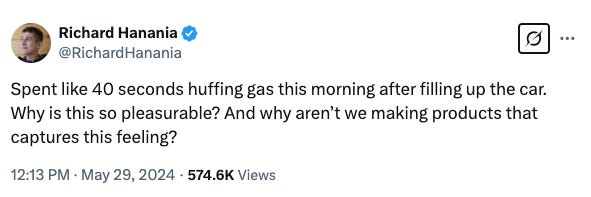

Hanania is, of course, infamous on the left for his past of posting incel-style race science on white supremacist forums as a younger man, for his crusade against wokeness, for his libertarian anti-socialism, and for his outré takes on Twitter.2 I first encountered him through the tweets, which gave outrage-bait but also a kind of earnestness that could be charming and amusing:

I am skeptical of the way Hanania and other libertarians treat evo-psych and microecon as the pure teaching of natural science and the uncomplicated laws of nature. I disagree with his anarcho-neoliberal celebration of unregulated capitalism as much as I disagreed with the Cato people and the Kochs in the 2010s. In a recent post, Hanania rues that Trump and Musk’s irrational firing of Department of Education workers will lead to the de facto forgiveness of student loans—probably the single political issue by which I am most existentially affected.3 Hanania’s support for cutting government and his resulting flirtation with Trump, whatever his thoughts now, were always idiotic. I could extend this paragraph almost infinitely, but the point is that I continue to disagree with him on the substance of almost every major political issue.

Nevertheless, Hanania’s defense of “elite human capital” seems in increasingly refreshing contrast to the tenor of the moment among certain littéraires, with its portentous embrace of irrationalism, loopy political prophecy, and attempt to instrumentalize destruction for boutique fantasies. Hanania was skeptical of the stated intent of DOGE and described it as a kind of “right-wing DEI” in that it mostly amounted to a bid for ideological control over the federal bureaucracy. In the past few weeks, he has mounted an increasingly despairing critique of Elon Musk himself:

A liar under normal circumstances would try to hide the fact that he’s lying. Musk, in contrast, is something much worse. He’s a man who has contempt for the entire concept of truth, and doesn’t care if the world knows it, as he poisons the public square. …. What all of this means is that the harmful effects of Musk’s influence go beyond policy disagreements one may have with him, and get to the question of whether rational thinking about political, social, and economic issues is even possible in the world he is trying to create.

He has also backtracked on his previous optimism about the Silicon Valley right. “The policy implications have been a mixed bag. But one thing we can say for certain is that having some of the most accomplished people in business come into the tent has somehow made the Right much dumber.” Though still clinging to his support for unlimited money in politics, Hanania recently argued that being a billionaire makes one especially susceptible to epistemic closure and thus rich people are a worrying force in democratic politics. He even adds: “I think left-wing billionaires are probably less likely to fall into this trap. This is because they have certain psychological and ideological commitments that stop individuals from becoming megalomaniacs.”

I don’t mean to overly congratulate Hanania for these specific conclusions, most of which have long been obvious to liberals and especially to the left. You could say his flirtations with Trump were also an attempt to instrumentalize something clearly stupid and unhinged for his boutique fantasies.4 One wonders what he has been doing since 2000, a quarter-century in which the American right has been on an uninterrupted descent into ever deeper circles of stupidity, craziness, and cynicism. And if the left’s institutions and people are so obviously morally and intellectually superior to the right, if they are the type of people he identifies with, has he ever considered that they…might also have good, evidence-based reasons for believing what they do, ones that he continues to dismiss with breathtaking ignorance?

But I am more interested in how Hanania thinks, what we might call his ethical or even aesthetic approach to politics. This is something he thinks about as well, and one of the things that makes his writing stand out despite our substantive and methodological agreements. From his post on Musk last week:

Even if we get a smaller and less intrusive government in the end, and that’s far from certain for reasons discussed above, I truly hate the thought of living in the kind of idiocracy that Musk is creating. People are usually involved in politics because they have an aesthetic preference for the world they would like to see, and I don’t want to live in a society where half the political spectrum operates in a constant haze of lies and misinformation, as the most shameless grifters and liars rise to the top. Liberals may in many cases want to censor certain ideas and not treat them fairly. This is a lot less horrifying than a new influencer-driven culture where no one cares to censor because truth has no hope of winning out against a constant avalanche of lies anyway.

Again, nothing many a resistance liberal didn’t say in 2016-2020, but it has a different resonance for me than it did then in part because of what I perceive to be the extremely cynical and myopic fellow-traveling of people who should know better with this “vibe shift,” the whitewashing of a possibly irreparable breakdown on some vague hope that it will take out a few things they personally dislike.5 In spite of what I think would be the ugly consequences of some of his ideas, Hanania’s animating impulses seem to be earnestly rational and liberal. His elitism is about personal striving for excellence; he doesn’t seem overly enamored with money or the wealthy, or have much taste for domination of his opponents if it involves a corroded and dishonest form of combat. He is an institutionalist who treats politics as something where the details matter and have consequences, and mostly respects people who adhere to the norms of intelligence and expertise. He seems to recognize that a right-wing assault on anyone associated with thinking and expertise is a world even a right-wing intellectual won’t want to live in.

There’s been a lot of hot air in the past year about an unleashed cultural vitality, a spiritual awakening, a “new romanticism’” and the like in the past year, and some of those types have greeted the new Trump administration as a necessary slate-cleaning even if they don’t explicitly support Trump himself. That overlaps significantly with what I call the “Substack ideology,” the notion that anyone who has elite credentials or works in institutional cultural production is corrupt or artistically bankrupt and needs to be swept away. The latter is partly a sociological war of position waged by people who see themselves as outsiders in a time when cultural production of almost every kind has been gutted and devalued by the market, from academia to journalism to publishing. It’s also probably an understandable desire to hold on to hope that there is some kind of positive horizon to look toward, that we are not headed for unmitigated doom. A spectral continuation of 2010s socialist hope of breaking out of the end of history, without the earnestness or substance. I get the impulse, but turning to anti-politics because politics is bleak is not an avant-garde move. It’s preemptive surrender.

Though late to the party and still failing to see that the “idiocracy” he decries is a result of the triumph of some of his own political ideas, at least Hanania is not pretending we should just look on the bright side, that this type of brainless techno-authoritarianism couldn’t plunge American political culture into an abyss of permanent cynicism. As John Ganz, who Hanania attacked last week, put it: “When we’re faced with a constant spectacle of corruption and idiocy, it’s far too much to ask us to pretend something spiritual is happening, some kind of sublime release of vitality. That seems akin to dancing in an explosion of sewage as if it were a cleansing rainstorm.”

To Hanania, I’d say: congratulations on realizing the right is for dummies and billionaires in politics are bad; maybe it’s time to follow your own arguments to their logical conclusions?6 And to the new-era-of-freedom-and-cultural-vitality people, I’d remind you you’re “elite human capital,” too, and the war on the professional-managerial class you’re fellow-traveling with, whatever your “sophisticated” reasons for doing so, is a war against you and everything you care about.

This was basically the argument Julian Sanchez made that started the 2010 “epistemic closure” debate among young right-leaning journalists and bloggers. That debate presented the right’s closure to empirical information as a new phenomenon, but in retrospect it was probably a cyclical generational reckoning with the historical centrality of anti-intellectualism to American conservatism, the political parallel to the cyclical generational reckonings with the anti-intellectualism of American evangelicalism.

Hanania has repudiated these views, though many leftists accuse him of simply trading them for a milder language of IQ and biological differences. I also read claims related to the latter with a high degree of skepticism, but don’t think they’re necessarily the main thing a leftist should object to in Hanania’s worldview.

It should be no surprise to find a neoliberal like Hanania defending federal bureaucracy on the grounds that you need state capacity to carry out socially regressive policies. Neoliberalism is often misunderstood as being about “slashing the state” when it is actually, as Quinn Slobodian has long argued, about using the power of the state to “protect” markets from democracy.

Who, by the way, is still a libertarian in 2025?

As I’ve written before in more piecemeal form, I think this perspective depends on an extremely short-term historical consciousness that gives far too much weight to the excesses of liberalism in the 2010s, in regards to which we were already seeing a course-correction well before the election. As irritating and counterproductive as some of the things that happened during the “woke” moment were, they are not even in the same universe as the censorship, ideological purification, and utter disregard for norms of debate that have been core to the modern American right for decades, and are even more pronounced in the post-literate, post-truth instantiation of it that Trump and Musk represent. That is not to excuse the counterproductive ideological conflagrations on the left during the 2010s, nor the extent to which liberalism began to imitate MAGA and abandon its traditional skepticism for influencer-driven conspiracies. It is to say that even so, the notion that anyone who cares about thinking, art, ideas, free speech, etc are better off with MAGA should be treated with all the contempt such an absurdity deserves.

Fortunately, this is America, and you have two neoliberal parties with different vibes to choose from!

The great paradox of American politics is that you have one party that panders to a bunch of people who think 5G is giving them cancer and another party that actually passes laws that will make your 5G internet go away.

https://www.theverge.com/2025/1/17/24346159/att-new-york-affordable-broadband-act-5g

"Who, by the way, is still a libertarian in 2025?"

There aren't many ideological libertarians, but there are many people who wouldn't want their taxes increased to pay for student loan forgiveness and other such things, including many of the newly converted high-income Democrats.

Does anyone who thinks we’re seeing “unleashed cultural vitality” because of the “death of woke” or w/e have any examples of like… cultural accomplishments? I suppose they could claim they haven’t had enough time at the wheel, but still.